Beyond Good Intentions

One of my major concerns with Effective Altruists is their lack of epistemic humility. They exhibit unwarranted confidence in their ability to reason about problems, which subsequently results in the absence of any error correction mechanisms.

In the spirit of Popper and Deutsch, I believe that error correction is of paramount importance in all our endeavors. For instance, it is the very reason why freedom of speech is so crucial. The loss of freedom of speech results in the loss of our ability to correct errors pertaining to certain subjects.

Error correction is also the most compelling argument in favor of Democracy. To put it succinctly, Democracy is not about selecting the most exceptional leaders, but rather about the ability to remove ineffective leaders and alter detrimental laws without resorting to violence. It is fundamentally about the ability to correct errors.

Telescopic Philanthropy

In Effective Altruism, the following thought experiment is used to establish a fundamental principle. Consider the scenario of encountering a child drowning in a pond; the moral imperative to attempt a rescue is clear. However, the question EAs raise is whether the location of the child – whether geographically distant, such as in Africa, or temporally distant, such as the future – affects our moral obligation to aid. The seemingly obvious conclusion that Effective Altruists reach, is that the location of the child should not matter. In other words, the moral worth of individuals should not depend on their place or time of birth (future lives matter!). That’s why EAs often strive to help individuals in, say, Africa, as they have determined that the same amount of resources can save more lives in these areas compared to others, such as America.

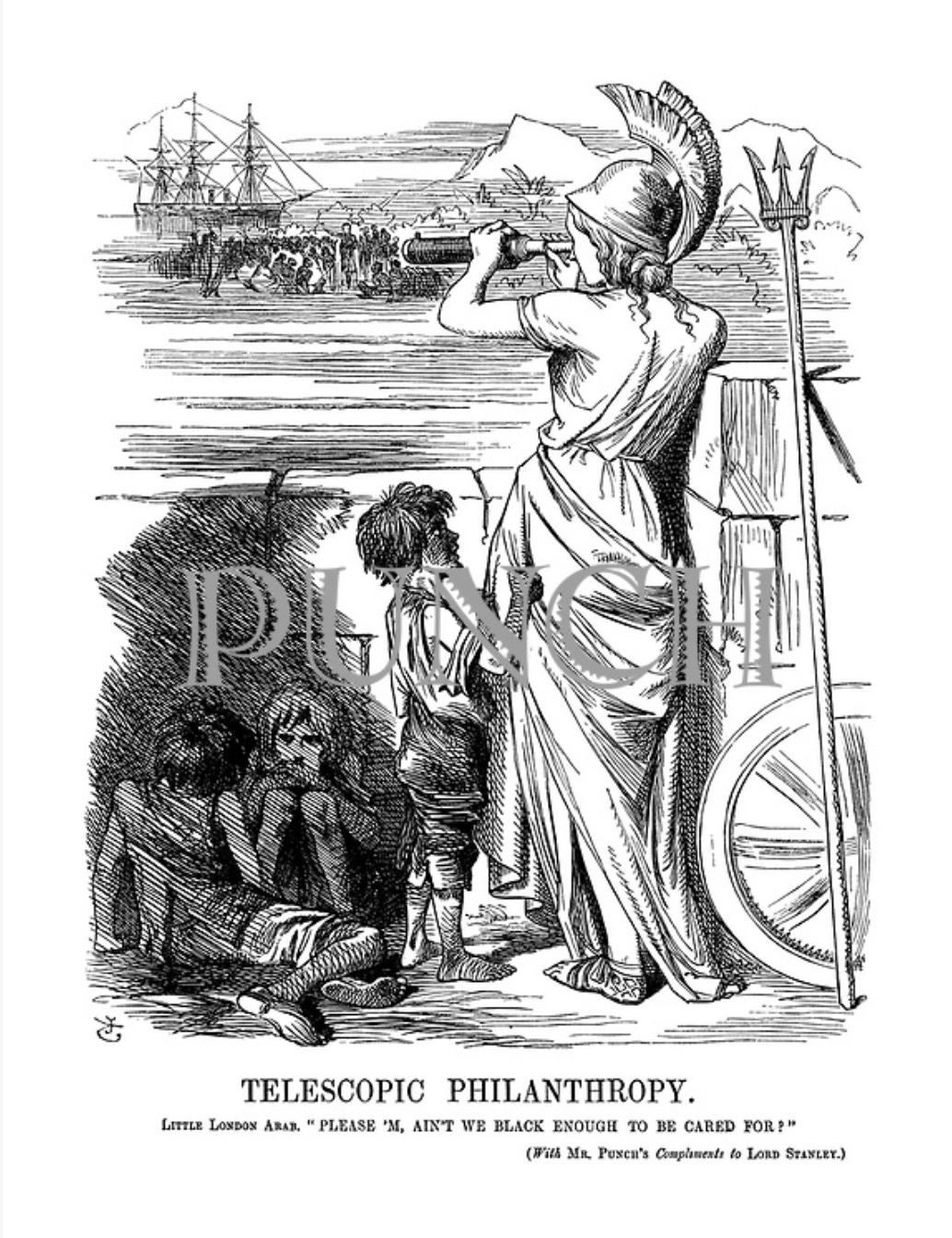

The concept, except for the importance placed on future lives, is not novel. Charles Dickens satirized this idea, which he referred to as “Telescopic Philanthropy,” in his 1852 novel, Bleak House. However, it is unlikely that even Dickens could have foreseen the extent to which this concept would be taken in the 21st century. A cartoon by John Tenniel, from the Victorian-era, lampoons this concept (Punch magazine):

The cartoon reads, “Please ’M, ain’t we black enough to be cared for?”

I think a modern, politically correct version (maybe printed on t-shirts?) could use my favorite line from the New Yorker piece about the leader of Effective Altruism, William MacAskill:

We passed People’s Park, which had become a tent city, but his [MacAskill's] eyes flicked toward the horizon.

It fits almost too perfectly. As we know, there are no good new ideas; only bad ones. But even most bad ideas turn out to be old.

The Means of Error Correction

Thus far, we haven’t pointed out any specific issue with Effective Altruism. We have merely shown that some old white guys made fun of it in the past under the name of telescopic philanthropy. But let’s not take their word for it: Plato, Aristotle, Socrates? Morons!

The primary challenge of attempting to help people who are temporally or geographically distant is the difficulty in determining whether our help is effective. Without feedback and error correction, it is possible to inadvertently worsen the situation without realizing it. In fact, I would argue that this occurs frequently.

That’s why in my previous critique of Effective Altruism, To Fix The World, Fix Philadelphia, I suggest focusing efforts on assisting homeless drug addicts in Philadelphia:

Another big advantage of working on my problem over working on AI alignment is that it is concrete and progress is easily observable – anyone can just drive through Philadelphia. For AI alignment, on the other hand, nobody even knows what progress looks like.

The inability to observe progress, or even to identify what constitutes progress, impairs our ability to implement error correction mechanisms. This poses a significant challenge.

A passage from Herbert Spencer’s book Social Statics (which bears the very catchy subtitle “The Conditions Essential to Happiness Specified, and the First of Them Developed”) comes to mind:

Those too were admirable motives, and very cogent reasons, which led In our government to establish an armed force on the coast of Africa for the suppression of the slave trade. What could be more essential to the "greatest happiness" than the annihilation of the abominable traffic? And how could forty ships of war, supported by an expenditure of £700,000 a year, fail to wholly or partially accomplish this? The results have, however, been anything but satisfactory. When the abolitionists of England advocated it, they little thought that such a measure instead of preventing would only "aggravate the horrors, without sensibly mitigating the extent of the traffic;" that it would generate fast-sailing slavers with decks one foot six inches apart, suffocation from close packing, miserable diseases, and a mortality of thirty-five per cent. They dreamed not that when hard pressed a slaver might throw a whole cargo of 500 negroes into the sea; nor that on a blockaded coast the disappointed chiefs would, as at Gallinas, put to death 200 men and women, and stick their heads on poles, along shore, in sight of the squadrona. In short, they never anticipated having to plead as they now do for the abandonment of coercion.

Imagine if that horrible unintended result had been unnoticed due to the distance of those affected or the opaqueness of the causal relationship. We Germans even have a proverb for that: “Gut gemeint ist das Gegenteil von gut gemacht.” (“Well-intentioned is the opposite of well-done.”)

I wrote in the above-mentioned essay:

It is not easy to fix Philadelphia (and other cities like it) as it requires fixing our institutions. The problem is not, as many EAs believe, solved by giving more money to charities. It is not a money problem. It is a problem of bad governance relying on broken institutions.

If you can address the situation without rebuilding our institutions, I am simply wrong and you have just improved the lives of many people before going back to AI safety research. But consider that people have been trying to solve this problem for decades, and I am convinced the situation has gotten progressively worse, not better.

If we are unable to effectively help individuals in our immediate vicinity, it would be unwise to presume that we can help those who are far away, without the ability to correct errors. Such an arrogant approach is a recipe for disaster.

Even in the case of addressing homelessness and drug addiction in cities such as Philadelphia or San Francisco, many people fail to discern the causal relationship between their well-intentioned actions, such as donating money, and the exacerbation of the problem. An example of this is the provision of clean needles to drug users, a common practice among charitable organizations. While the intention is to prevent deaths from dirty needles, it also makes drug use more accessible and comfortable, thereby increasing the number of addicts. This unintended outcome, even in such a simple case, highlights the need for error correction mechanisms.

I once again find myself in the position of urging Effective Altruists to try their hands on a more modest problem than “saving the world”: helping the drug addicts in their cities. Put differently, EAs should try to fix this situation.

I again predict that the problem is not easily solved with more money because it requires reforming institutions. Furthermore, I hope that once EAs start working on this problem, they realize that their current efforts to save the world, e.g., “pandemic prevention,” are making matters worse. But I won’t hold my breath.