Why I Didn’t Invest in Substack

Last week Substack announced that they were raising a community round via the crowdfunding platform Wefunder making it possible for non-accredited investors to participate. It seems to have gone well; the Wefunder page shows $7.5M raised from 6.5k investors. These numbers are very rough as one doesn’t have to commit money to reserve an allocation, but I’m nonetheless happy for Substack that they seem to have exceeded their goal of raising 5M. However, despite my appreciation for their product, as evidenced by the fact that I’m writing here, I didn’t invest.

Crowdfunding

In the venture capital sphere, crowdfunding carries a strong negative connotation (although this is changing a little). Startups resorting to this method signal an inability to secure funds from “real” investors. Ideally, a startup would prefer backing from firms like a16z and other angel investors, as this not only provides financial support but also valuable advice, a useful network, and a signal that helps with recruitment.

Consequently, deals on crowdfunding platforms such as Wefunder or Republic are those that traditional VCs have passed on, likely due to bad terms or an unappealing business. Extremely rare exceptions do exists, such as Gumroad, who raised 1M from Angels like Naval Ravikant and Jason Fried, followed by 5M from their users at the same $100M valuation. If you get to invest on the same terms as Naval and Jason, you can be sure that the deal isn’t that bad.

The case of Substack was different. They raised their whole round without the participation of existing investors like a16z. As a retail investor, you should as yourself: why? I have no insider information, but one explanation is that the existing investors didn’t want to invest on these terms. They might even have encouraged Substack to raise via crowdfunding because that keeps the valuation high.

Another explanation for such a community round is that Substack wants to let their user participate in the upside. The users are, after all, what makes a platform like Substack grow, so it can make sense to let users invest in the hopes that they promote and grow the platform even more.

The first explanation strikes me as more plausible, but since I have no insights into their finances and runway, I’m merely guessing here. Nonetheless, we will take a closer look at the incentives at play and at the terms of the deal to see why I chose not to invest.

Up Only

A weird consequence of the way private markets work is that founders and investors never want a startup to do a down round – a funding round with lower valuations than the previous one. This extreme aversion to down rounds stems partially from the emphasis on growth in the startup world but also from the way venture capitalists report returns to their limited partners (investors in their fund). Matt Levine describes it well in Money Stuff:

One reason it’s a thing has to do with the accounting conventions of the venture capitalists themselves. If your VCs invested at a $250 million valuation, and you do a new round at a $150 million valuation, then they have to write down their investment by 40%. They have to tell their own investors that they lost money for them; their assets under management have gone down and they can’t charge as much in fees. They would prefer for their investments only to go up. […]

One cynical way to understand private investing generally is that private investment firms — venture capital, private equity, private real estate, etc. — charge their customers high fees for the service of avoiding the visible volatility of public markets. If you invest in stocks, sometimes they go up, and other times they go down. If you invest in private assets, they don’t trade; sometimes they go up (because companies raise new rounds of capital at higher prices), but the companies and the investment managers take pains to keep them from going down. This makes the chart of returns look much nicer — it mostly goes up smoothly — so the private investment managers can charge higher fees.

As a consequence, it’s not always advantageous for a startup like Substack to raise at the highest valuation they can. Raising funds at an inflated valuation makes it more difficult to raise at an even higher valuation in subsequent rounds, especially if (as in this case) the market changes.

Simply put, the actual valuation of a startup is less important than the fact that the valuation only goes up. As my dad used to tell me when I was a young kid waiting for the rain to stop: the derivative is more important than the absolute value. (In addition to explaining venture capital and startups, this turns out to be an important life lesson.)

A good rule of thumb: The derivative of a startup’s valuation (and users, revenue, etc.) is either positive or the startup has failed.

Substack’s Valuation

Equipped with this knowledge, we can now better understand the position Substack found itself in (assuming they don’t have much runway left). In 2021, they raised a Series B from a16z at an exceptionally high valuation:

Substack raised a $65 million Series B round led by Andreessen Horowitz in September 2021. The post-money valuation on its Series B round was $650 million, representing a ~70x multiple on $9 million of revenue at the end of 2021.

For those not in the know, a 70x multiple is insanely high, even for the 2021 bull market. This put Substack and its investors in a difficult situation. As the market shifts, such multiples are no longer possible. Thus, a crowdfunding round (at $585M) was likely the only way to avert a drastic down round.

Something that stands out when reading through Substack’s Wefunder page is that they don’t mention their revenue (apparently, they will release their financial statement later). That doesn’t inspire confidence. When raising later-stage rounds, where you have revenue, you have to share these numbers with your prospective investors.

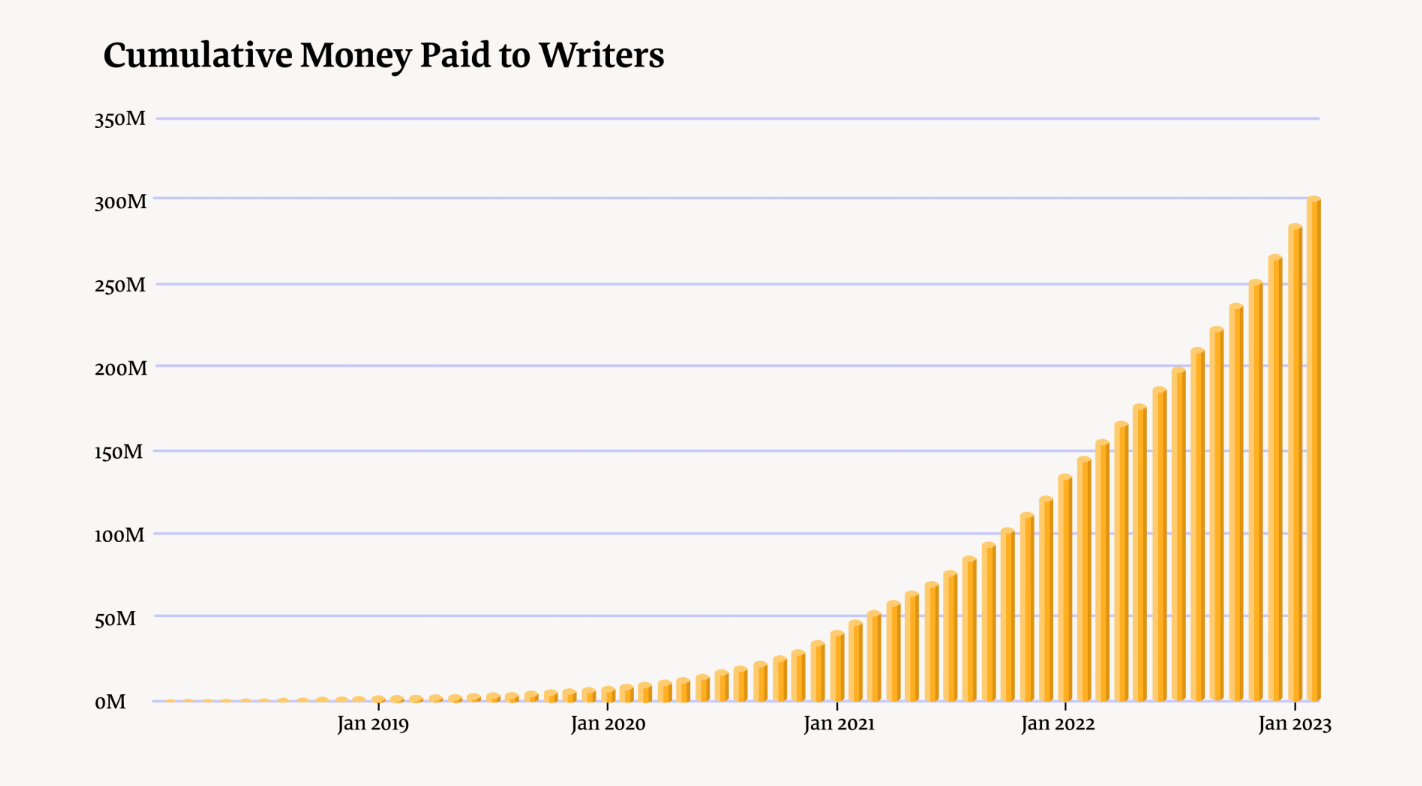

The only available method to estimate current revenue I found is by examining this chart they shared:

Be aware that this is a cumulative chart which should already make you suspicious. Cumulative charts always look great – they go up and to the right by definition. But they are mainly used to obfuscate the fact that the more informative chart – the absolute monthly numbers – doesn’t look that great.

Nonetheless, we can use this chart to do some math and figure out the rough revenue numbers. We see that they took 3 months to get from 250M to 300M – that’s ($50M / 3 = $16.6M) roughly $17M paid to writers last month.

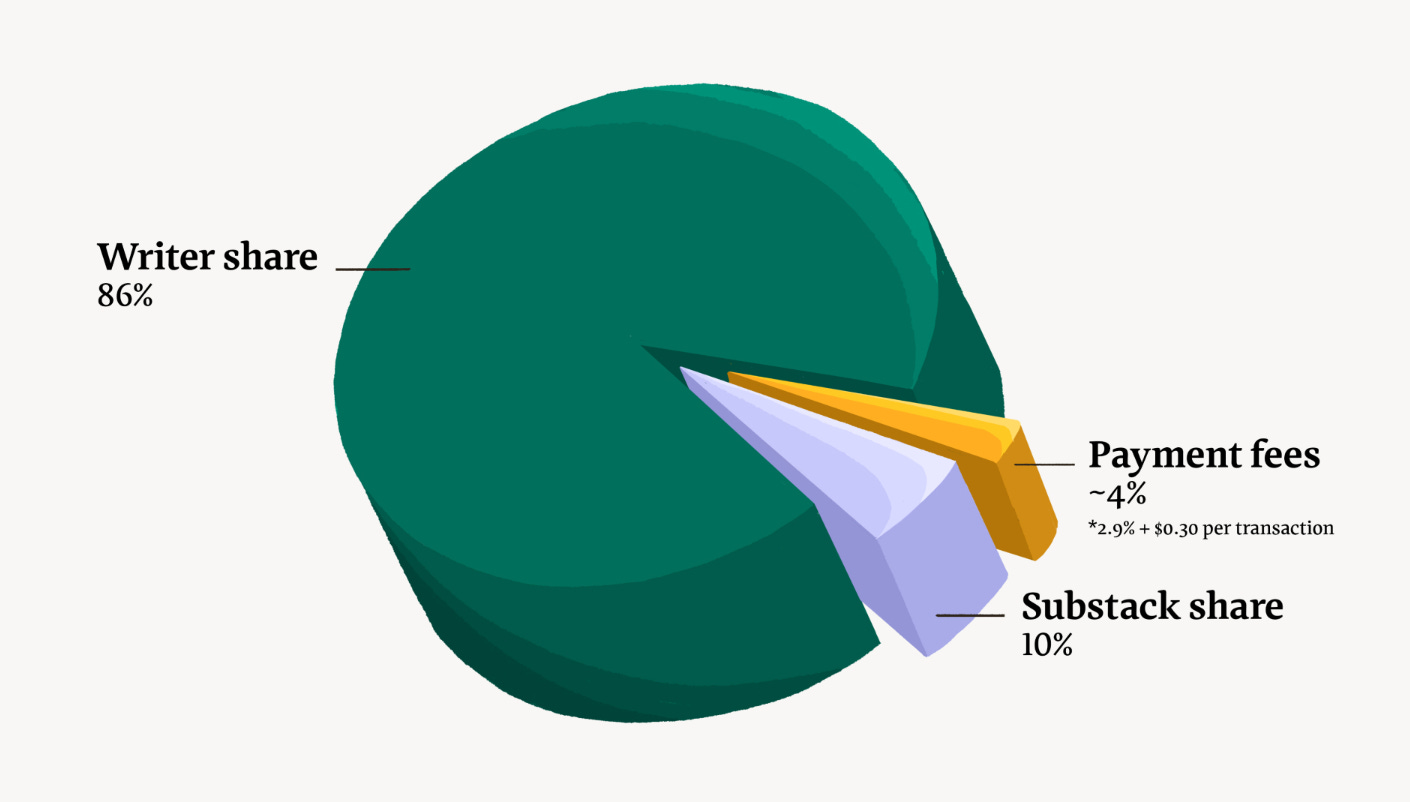

As this graphic informs us, Substack takes 10% of the money paid to writers.

That’s ($17M x 10%) $1.7M of revenue for the last month. (The real number is probably slightly different as Substack has special contracts with big writers, but let’s not worry about that here.) Annualizing the monthly revenue ($1.7 million x 12) yields $20.4M in annual recurring revenue (ARR). Substack’s pre-money valuation – i.e., before the money goes in – was $585M. Let’s be generous and say that makes it a $600M post-money valuation, so we can easily compare it to the $650M valuation from their Series B. The multiple we get for this round is ($600M / 20.4 = 29.4) roughly 30. That’s significantly lower than the 70x multiple a16z paid for it in 2021.

Determining whether the multiple is too high or too low comes down to judging the business – as hinted at above, for startups that mainly means looking at growth. For those unfamiliar with current market multiples, this might seem like a good deal, but I don’t think it is.

One method for gauging multiples is by examining those of public tech companies (although these often lack comparable growth). Alternatively, we can look at what other experienced people are saying. For instance, I tend to agree with Parker and Alex who suggest that around a 10x multiple for a platform like this seems reasonable. That would make Substack worth $200M, not $600M.

Good Products May Be Bad Businesses

Substack’s main issue is the absence of a lock-in effect and, consequently, limited pricing power. Ironically, that’s also the reason I like Substack as a user. The platform is built on email, allowing users to leave and take all their subscribers with them. In contrast, leaving Twitter results in losing most if not all of your audience. From the user side, the reliance on email is a feature; from the business side, it’s a bug. If Substack were to increase its fee to 30% (the fee Apple takes in the Appstore), everyone would simply leave. This means that even if Substack keeps growing its users, it can never charge them much money. Good for the users; bad for the business.

I still hope Substack will succeed long term, particularly after witnessing Twitter’s reaction to the announcement of Substack’s Notes feature (which resembles Twitter). For at least 24 hours, Twitter users were unable to like or share tweets containing Substack links – a response that highlights the need for a more open alternative. (At the time of writing, embedding tweets in a post, as was previously possible, still isn’t).

We will see if Substack can overcome Twitter’s strong network effect, something Nostr couldn’t. But keep in mind: People underestimate the strength of the network effect until they try to leave.

Thanks to Thilo Konzok for edits and contributions.