We Used To Eat A Lot More Without Becoming Obese

The mainstream theory regarding the obesity crisis is that people consume excessive calories and move insufficiently - “calories in, calories out.” Alternative nutritional perspectives, such as Keto and Veganism, challenge this narrative only to some extent. Keto proponents attribute obesity primarily to excessive carbohydrate intake, while vegan advocates point to excessive meat consumption. Despite divergences on the impact of specific food groups, there is a near-universal consensus on the overconsumption of sugar in modern diets.

A problem with all of these theories is that historically we used to eat a lot more – including a lot more carbs or sugar.

Teeth

In a great series of posts about the mystery of obesity slimemoldtimemold hints at this paradox:

If we go back further, the story actually becomes even more interesting. Based on estimates from nutrient availability data, Americans actually ate more calories in 1909 than they did in 1960.

Unfortunately, this point is not discussed further because good pre-1960s data is hard to come by.

Back in 2021 when I read that post, I didn't think much of it finding “nutrient availability data” was not very convincing. A few days ago, however, I stumbled on “Remarks on the Influence of a Cereal-Free Diet Rich in Vitamin D and Calcium on Dental Caries in Children.” May, the wife of Sir Edward Mellanby, known for his discovery of vitamin D, conducted extensive research with her husband, primarily focusing on the effects of vitamin D on bone and dental health. In this particular study, Mellanby explores the impact of a reduced cereal intake on dental caries. The experiment was a success:

A group of children averaging 5 1/2 years of age were given a cereal-free diet rich in vitamin D and calcium for a period of six months. The teeth of the children were defective in structure (hypoplastic), and much active dental caries was present at the beginning of the investigation.Initiation and spread of caries were almost eliminated by these diets, and the results were better than those of the previous investigation in which-the vitamin D alone was increased in a diet containing bread and other cereals.Active caries was arrested on this cereal-free diet to a greater extent than in the previous investigations, when cereals were extensively used. We wish to express our gratitude to the Medical Research Council for making this investigation possible.

Today, it is understood that the result can be attributed to the high phytic acid content in cereals, which binds minerals such as calcium, iron, and zinc, impeding their absorption. This connection, however, was not established in 1932 when Mellanby conducted her research. The critical role of phytic acid was only discovered later by Alan Wise who published “Dietary Factors Determining the Biological Activities of Phytate.” in 1938.

How Much Did We Eat?

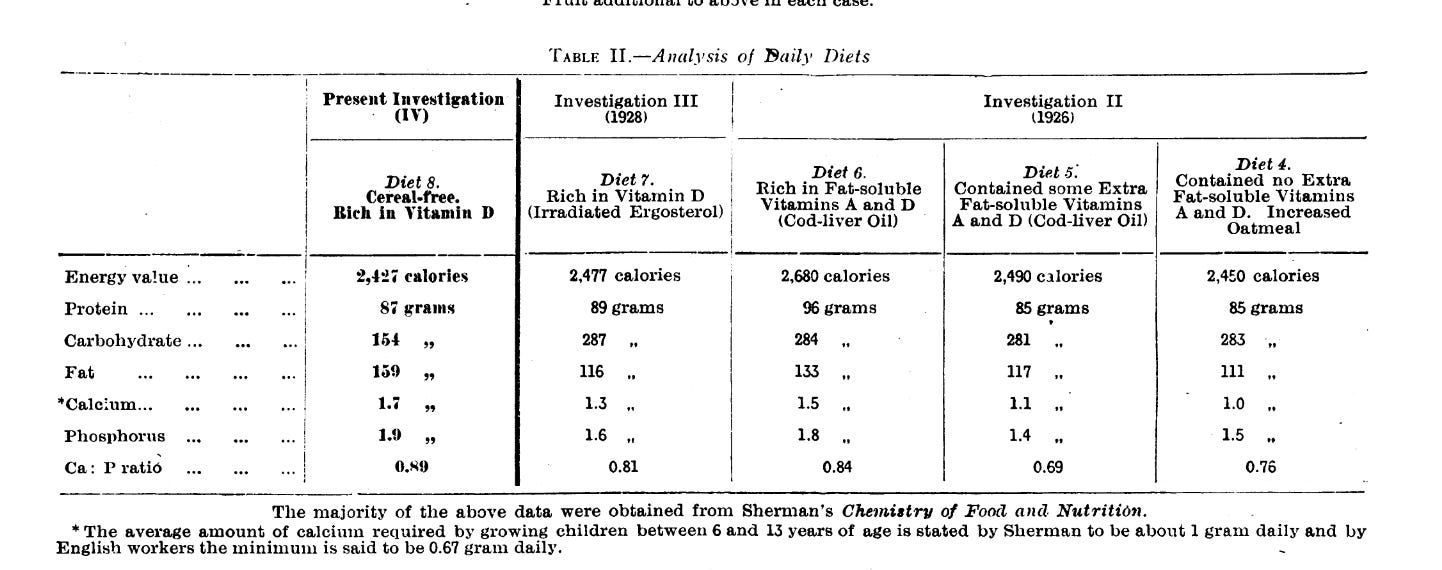

What has this all to do with obesity? The study was done on 5-year-old children in an institution where they had full control over what they ate. So how much did (non-obese) children in 1928/1929 eat?

For reference, the American Heart Association states that children between 4 and 8 need 1400 calories. These kids ate 2.5k calories.

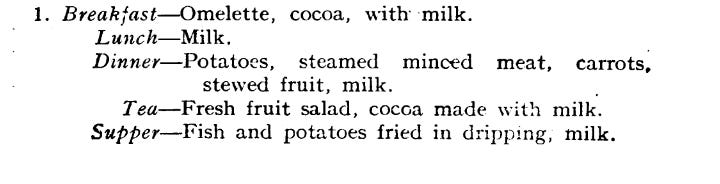

The paper also provides a few examples of diets for a day. (Note that back in these days “Dinner” sometimes referred to the main meal of the day regardless of time and “lunch” designated something more like a small mid-morning snack.)

Another intriguing study I came across, conducted by the Ministry of Health in 1953, specifically examined the correlation between the caloric intake of industrial workers and the physical demands of their labor.

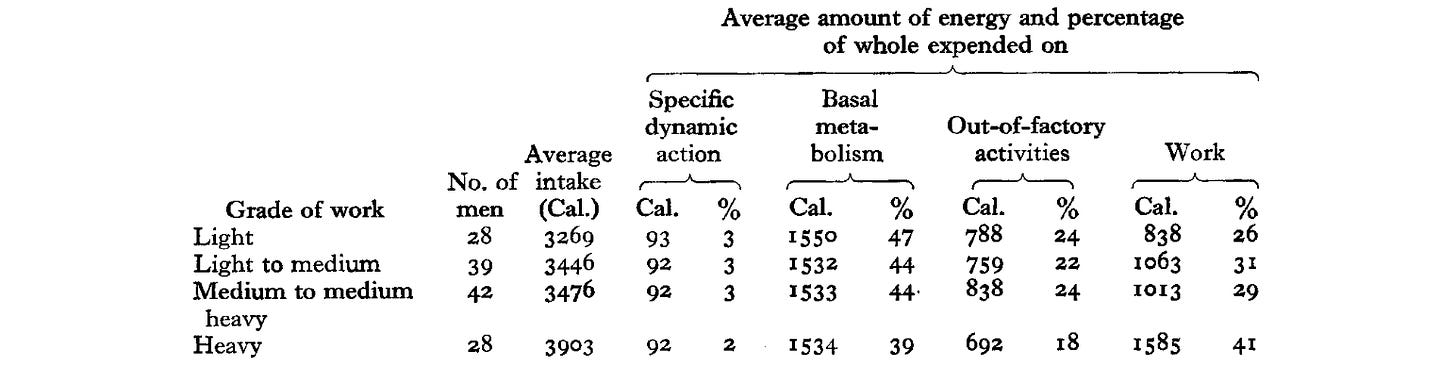

Here is the most interesting table:

Even those in “light” labor roles consumed 3.2k calories daily. Examples of such jobs included toothbrush filler, rotary machine operator, and polisher. While these tasks may not be as physically undemanding as sitting at a computer, they are not much more demanding. Notably, the average height and weight of these men were 170 cm and 66 kg, respectively. For men of this stature to eat 3,200 calories daily without becoming obese, (in an era where unlike today “workouts” were not a thing) seems almost inconceivable. For comparison, modern calorie calculators suggest a daily intake of 2,300 calories for a moderately active 25-year-old male with similar physical measurements.

As an aside: The skeptical reader might have noticed that even though I discussed in my last post why I consider surveys bullshit, I now cite a study that is using surveys to find out how much people ate. Do we have any reason to believe that this survey holds more evidentiary value than the usual bullshit online survey? I think we do:

A record was obtained of the food eaten inside and outside the home and the beer drunk by each subject for I week. The record of the home diet was collected by the weighing method of Widdowson (1936) and of Beltram & Bransby (1950),but measuring glasses were provided for measuring liquids. The wife or mother made the measurements and kept the records; she was visited almost every day by a field worker to ensure that the information was being properly recorded. No record had to be discarded as unsatisfactory. In each factory where there was a canteen, samples of the food served during the period were weighed on each day that the survey was being made in that factory. The men in one factory had their midday meal in two neighbouring cafhs, and the proprietress of each caf6 kept the necessary records. In another factory the men ate in a neighbouring one and, again, the weights of the foods provided were obtained. The men on being interviewed about their out-of-factory activities were asked to say also what beer they had drunk.

A stark contrast to the “How much did you eat of food X in the last year?” online surveys that are used by famous nutritionists like Dr. Rhonda Patrick to make ridiculous claims such as “For every 100mg of magnesium intake, there was a 24% decrease in pancreatic cancer risk.” The “scientists” of today are truly marvelous.

For some more interesting evidence of pre-1970 high-calorie consumption, watch this great video by Analyze & Optimize.

Metabolism

The most compelling argument I've encountered for the paradox of declining calorie intake amidst rising obesity rates comes from the Ray Peat community. They propose that people historically had significantly faster metabolisms. This theory also explains the observed decrease in average body temperature, from the standard 37°C in 1951 to 36.6°C by 2002.

The mainstream interprets the decline in average body temperature as beneficial, suggesting it may indicate reduced inflammation levels:

Although there are many factors that influence resting metabolic rate, change in the population-level of inflammation seems the most plausible explanation for the observed decrease in temperature over time.

Another alternative hypothesis attributes the decrease in temperature to diminished microbial diversity, a consequence of widespread antibiotic use.

However, explanations other than Ray Peat's don't account for our original obesity paradox. Accepting the metabolic perspective raises the question of why metabolic rates have declined. There is no strong consensus on this issue, with theories pointing to known culprits such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), bisphenol A (BPAs), and heavy metals.

Nonetheless, it seems improbable that too many calories in and too few calories out are the cause of modern obesity.

Edit: My language at the end is very sloppy. Strictly speaking, metabolism is still part of the “calories in/calories out” framework. It’s just that when people talk about CICO, they usually mean eating less and working out more. Increasing how many calories you burn by accelerating your metabolism is rarely the plan. Still, I was wrong to write, “it seems improbable that too many calories in and too few calories out are the cause of modern obesity.”