Breaking: Elon Musk is Not Stupid

We have recently been granted a glimpse behind the curtain of how arguably the best fundraiser in the world, Elon Musk, raises funds. Due to the lawsuit in connection with his Twitter deal, many of his private messages with friends and business partners were made public. We can see Elon Musk engaged in friendly informal chats raising billions of dollars for this new venture. He raises money not based on numbers or complicated models but based on vibes.

The whole nature of these chats – the casual tone in addition to the absence of any quantitative metrics – seemed strange to some, and almost offensive to others.

I want to stress, what’s striking here isn’t that Elon Musk is very stupid, which we knew, but that *literally all the rich people he texts* are also stupid. He lives in an echo chamber of pure stupidity.

elon musk’s text messages make him look dumb as hell but in his defense we only have his texts because he’s fighting a lawsuit for no good reason, that was launched because he backed out of buying twitter for no good reason, a deal he made for no good reason

The Atlantic summarized the reaction in an article titled Elon Musk’s Texts Shatter the Myth of the Tech Genius:

“It’s been a general Is this really how business is done? There’s no real strategic thought or analysis. It’s just emotional and done without any real care for consequence.”

The group of those who are angered by the messages is largely made up of the kind of people you would expect: Academics and journalists. In other words, people with no experience in real-world decision-making.

Aside from the fact that it is, of course, very reasonable to do a little less due diligence on one of the most successful entrepreneurs of our time, I would like to point out something else. Many of the people Elon is raising money from are venture capitalists, whose job has little to do with numbers. As Paul Graham, one of the most successful people in the space, put it:

I have never read a business plan or a balance sheet.

It is not that these metrics are completely irrelevant, it is just that other variables are way more important. Judging which variables really matter at the different stages of different companies is an art. Paul Graham, and most of the people in Elon’s chats, are the finest practitioners of this craft. They have, as far as that is possible, mastered it. Through years of experience and practice, they have achieved something I touched on in my essay The Death of Intellectual Curiosity: the simplicity on the other side of complexity.

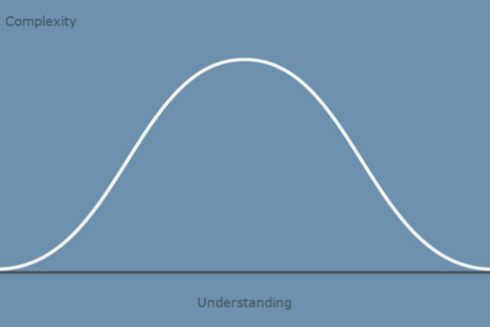

Take any real-world domain: in the beginning, your model is very simple and includes only a handful of variables. As you understand more and more about the domain, in this case, startups and venture capital, things get more complicated. You will find that the world is complex and that many variables can affect how well a startup will do in the future. You will also find that some of your assumptions were either too simplistic or just plain wrong. The number of variables you need to consider keeps increasing, making your “mental model” almost impractically complex.

However, if you carry on, you will notice something interesting: things become simpler again. You discover the domain-specific Pareto principle by developing a sense of which variables drive most of the outcome and which are unimportant. In short, you learn to separate the signal from the noise.

To outsiders, the result may look like the naive model you started with since the complexity is similar, but that could not be further from the truth. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. expressed it beautifully:

For the simplicity on this side of complexity, I wouldn't give you a fig. But for the simplicity on the other side of complexity, for that I would give you anything I have.

This type of simplicity is rarely encountered and almost never rewarded inside Academia, except in some STEM fields. From economics and virology to climate science, you see cargo cult scientists create almost incomprehensibly complex models, which do only one thing consistently: fail. Complexity is treated as sophistication and simplicity as laziness or stupidity. In the real world, the simplicity on the other side of complexity is not evidence of stupidity, but of sophistication.

Academics too often mistake the confusing for the complex and the complex for the sophisticated.

This is not just a long-winded explanation for why “It’s Elon, bro!” is enough for most investors to wire some money. It is, more importantly, the explanation for why these investors are not stupid for doing deals this way.

Let me share another story to illustrate the point. When I get the chance to invest in a startup (a little more on that here), I sometimes ask Naval Ravikant for his opinion. Before texting him, I try to weigh the many pros and cons, frequently without finding a clear answer. He often replies with a short text that reads, “It’s a bad [or good] deal because of X.”

Now, I had considered X as well; it is in my “mental model.” The difficult part, the part that is almost impossible to figure out without experience, is judging the importance of X. I was worried about the complex interplay of many other variables when in reality they do not matter in comparison to X, which is frequently obvious only after he mentions it.

To outsiders, my approach – if I were to write it down – may seem more impressive because I take all these different factors into account, but that is an illusion. Focusing on one or a few factors is superior, provided – and that is the tricky part – they are the right ones. That is what makes the hard-won simplicity on the other side of complexity so impressive in practice, even though you might get called stupid for it in public.